If László Krasznahorkai’s latest novel is part of the continuation of his greatest texts, War & War and The Melancholy of the Resistance, he manages to make the world differently, through an extraordinary multiplication of perspectives and enunciations.

Funny and serious story of a universe that dislocates around an idiot (baron) and a madman (scientist), but whose writing tirelessly recombines the pieces. How to create infinity with finite.

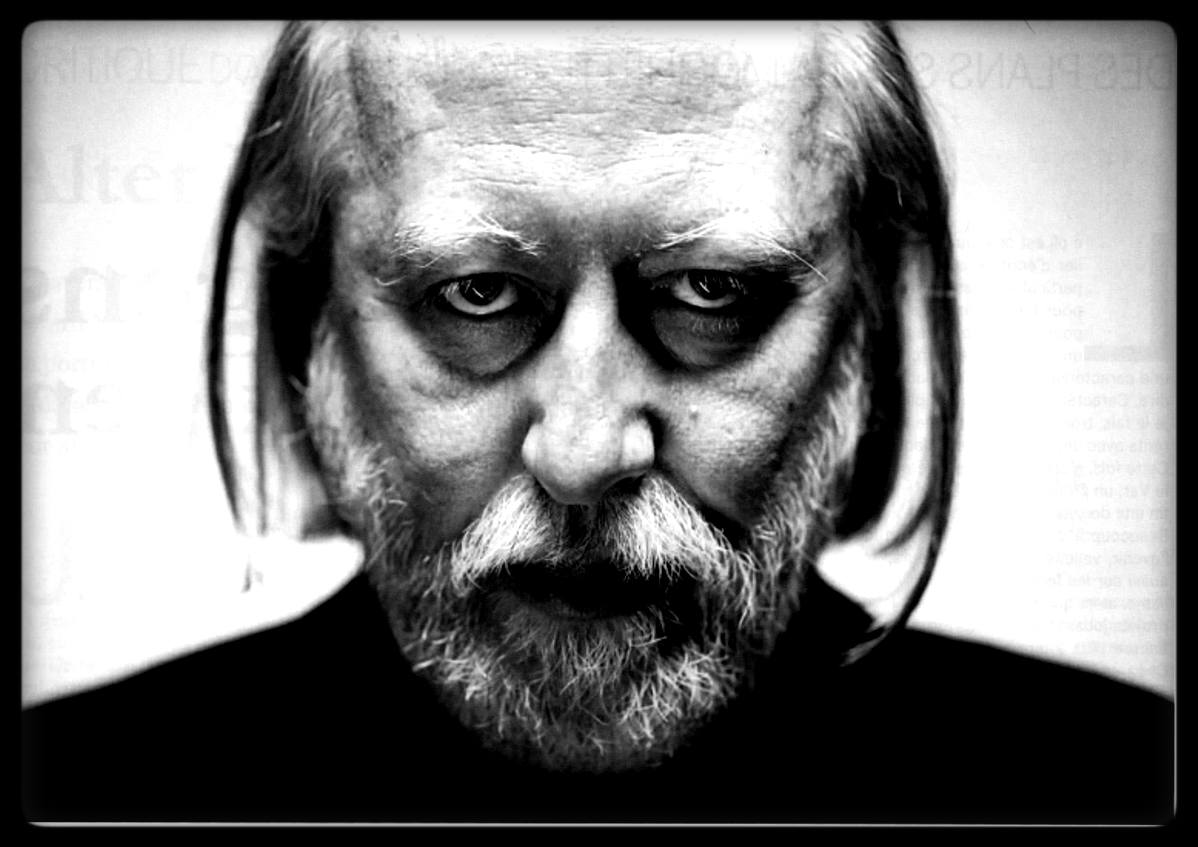

Text: Bastien Gallet

Translated from AOC.media: Le hasard et le miracle – sur Le baron Wenckheim est de retour de László Krasznahorkai by Ramona Frost for Futuristika.

It all begins with a thwarted will. In spite of himself, the man must resolve to approach the window, move the Styrofoam panel, look outside, because outside there is a young woman, his daughter, who, with a megaphone in her hand, is shouting, denouncing his faults, demanding accountability. We learn that he’s a famous professor, an unlikely world specialist in mosses, that he’s gone mad, that he’s left everything behind, that he’s taken refuge in a cabin in the middle of a bramble grove, to isolate himself as completely as possible from human affairs.

This first movement, which forces the professor to leave his cabin and wander the outskirts of the city, eventually leading him to the country’s capital, and which brings him back into the world against his own will, contrasts almost exactly with the book’s other great movement, that of Baron Wenckheim, who returns.

What does the sentence do? Several things. It makes heterogeneous perspectives coexist, holds them together, passes them seamlessly through one another, and thus equalizes and confronts them.

A departure versus a return, two opposing movements, both forced. The professor leaves because he’s being hunted by a local militia. The Baron returns because, threatened with imprisonment, he has had to flee Argentina, his adopted country. These movements, however, end up being willed, becoming wills, even desires: the professor’s immobility in a Budapest square as he listens to his daughter’s speech, which he didn’t dare look at through the window of his cottage; the Baron’s desire for Marika, his childhood sweetheart, whom he would so much like to see again. Whatever their driving force, these movements disturb the course of the world, moving crowds, arousing appetites, revealing connivances, enraging, inspiring dreams and delirium – in short, they produce a myriad of effects that László Krasznahorkai describes in great detail and from multiple points of view.

His writing becomes perspectivist. The third chapter, which describes the city on the eve of the Baron’s arrival, is one of the most virtuoso in this respect. Each paragraph embodies a new enunciation, sometimes blending several, using both first and third person, the whole composing a heterogeneous, dissonant chorus traversed by the Baron’s idiotic perspective, which all the others try to decipher without success. His ability to magnetize the most disparate movements around him reaches its acme in the welcome ceremony which, in the next chapter, brings together the entire town in front of the station: mayor, chief of the gendarmerie, motorcycle gang, carriage, choir, crowd and banners.

Of course, there’s a reason for this craze: everyone believes that the Baron is returning to donate his fortune to the town, a fortune he has in fact lost entirely in Argentina. His death, and the consequent discovery of his destitution, will produce an opposite movement of dispersal, culminating in the city’s annihilation. The idiotic movements of the Baron, whose journeys through the city defy all logic, become the very movement of the world, a world gone mad. With his death, which seals the victory of chance – he dies on a railroad track, struck by a crane car at full speed – the line of the universe becomes massively entropic.

Towards the end of the book, in the penultimate chapter, a gendarmerie sergeant assigned to the archives and a lover of the great Latin authors is reading a passage from Tacitus’ Annals when he is summoned by his captain. For several days, the town has been the scene of a series of unrelated events, crimes and depredations that have shaken public order. Unable to make sense of what’s happening, i.e., to correlate events with reasons and causes, the captain (and head of the gendarmerie) is ready to turn to Caesar, Tacitus and Cicero. Unfortunately, the sergeant, who certainly knows Latin but only wants “a few days off without pay”, can’t see how these authors could be of any use to them. The passage in question, the beginning of chapter 28 of the first book of the Annales – one of the few quotations in the book, along with that of the Hungarian poet Attila Józseph, to which I’ll return later – recounts an episode that would have provided the gendarmerie with the means to apprehend an unprecedented and highly uncertain situation.

“Tacitus was telling him: the night was threatening and would bring out the crime; but chance served as a calming influence. The moon was seen in a serene sky, suddenly ready to fade. This phenomenon, the reason for which he did not know, was for the soldier [Drusus] an omen relating to his present situation; he equated the eclipse of this star with his misery, and imagined that what he was pursuing would have a happy success, if the goddess resumed her brilliant brilliance. So they make the sound of bronze, the accents of trumpets and horns, alternately joyful or sorrowful, according to whether she appears brighter or duller to them; then, when the rising clouds hid it from their sight, they believed it to be buried in darkness, and, as one easily passes to superstition when one’s mind is once stricken, they lament and cry out that this is for them the harbinger of eternal misery and that the gods turn away from their crimes.”

The year was 14 AD. The legions of Pannonia have revolted. Drusus, dispatched by Tiberius, was unable to put down the revolt. Chance comes to his aid in the form of a lunar eclipse. For Drusus, the eclipse was a good omen, but it also terrorized the legionaries and enabled him to put down the rebellion. What they interpreted as a sign of destiny (fatum) was merely an effect of chance (fors), i.e. the natural order of things in all its unpredictability. Whether fate or chance, the eclipse eludes the grasp of human affairs, but influences its course. As Tacitus writes in the sixth book of the Annals: “For myself, I cannot decide the question of whether it is by destiny and its inexorable fatality that human things are governed, or whether it is to chance that their vicissitude is abandoned.” One of the historian’s tasks will be to preserve the weak power of human freedom between what astral configurations predict and what chance imposes.

Tacitus’ appearance at this point in the story is all the more interesting in that it, too, seems to be a matter of chance; unless we decide to relate them. Like the legionnaires described by the Latin historian, the city’s inhabitants are distraught by what is happening, even if what is happening has little to do with the effects of stellar movements. What is happening is that nothing seems predictable any more. Chance, which in Tacitus is the effect of an unknown order, becomes in Krasznahorkai that of a disorder that extends to the whole world. “Everything is falling apart,” he [the priest] wrote to the parish bishop, “we can no longer perceive the correlating link between things, what I mean is that everything that has stood up until now no longer stands up, we hear about horrible events but nothing is certain, we have no certainty that they really happened […].”

A disorder which, given what ultimately happens – the burning down and total destruction of the city with the exception of a concrete water tower – could very well be interpreted as fate, the sequence of unconnected events leading a posteriori to the disintegration of all existence within the city’s borders. Emancipated, chance becomes indistinguishable from destiny, a destiny that can be found under different guises from one of the author’s books to the next. For destiny cannot exist without agents, forces or characters, fools and prophets, who produce, reveal or amplify it. In Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming, the rise of disorder is linked to the baron’s return to his hometown and the exaggerated hopes he has aroused in its inhabitants. In The Melancholy of Resistance, it’s linked to the presence of the Prince, who has come with the traveling circus, whose prophecies arouse the crowds and set the town ablaze.

But these sometimes unwitting agents of chaos are also the physical forces that crush and dislocate all things. The Melancholy of Resistance thus concludes with an extraordinarily detailed description of the process of a body’s decomposition, from the “fortress” it was when it lived to the dissemination of all its constituent elements: “It was all there – although there was no longer an accountant to take inventory of its elements – but the original and truly non-reproducible realm had vanished forever, it had been crushed by the infinite force of a chaos that concealed the crystals of order, shattered by the irreducible and indifferent circulation that governed the universe. “

Krasznahorkai loves dissonant doubles. The idiot and the scholar, the baron and the professor.

Yet chance-destiny remains an ambivalent process. Disorder and destruction are just one of its possible slopes. There’s another: the miracle. In an earlier book, A Mountain to the North, a Lake to the South, Paths to the West, a River to the East, Krasznahorkai describes the hazardous sequence of events that, “apparently” by chance, produced one of Kyoto’s most beautiful gardens: the journey of the pollen strands from the Chinese province of Shandong to the small courtyard of a Buddhist monastery in Kyoto, which, after a thousand twists and turns, gave rise to the eight hinokis in the garden; the journey of the spores which, after several circumnavigations of the Earth, carried away by the jet-stream, landed around the trees and formed a “dazzling carpet of silvery moss”: “an incomprehensible and terrifying miracle”. The erratic movements of the Prince of Genji’s grandson, the novel’s main character, through the meandering monastery follow the same erratic logic as those of the Baron in his hometown. He misses the garden just as the Baron misses Marika, albeit for different reasons. In both cases, chance prevents movement, the grandson from enjoying the garden and the Baron from reaching Marika.

The “irreducible and indifferent circulation” described at the end of The Melancholy of Resistance also produces miracles: the whale that Janos Valuska visits in the middle of the book in its huge tin box (a reminder of the whale the author saw as a child, as recounted by the lecturer in Universal Theseus) and, more generally, all things whose beauty captures a body on the lookout – a Noh mask, an Andrei Rublev icon, an altarpiece by Perugino, a Bach aria, the Great Egret in Kyoto etc., epiphanies that Krasznahorkai described in Seiobo There Below. Such epiphanies are rare in Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming they affect only the baron, the only person who can still be amazed by what he sees. At the beginning of the book, through the window of the train taking him home over the Hungarian border, he observes the landscape, deserted fields and ruined farms, but suddenly the sky opens up and rays of light reach down to earth, a nimbus appears that reminds him of the holy images of his childhood, his heart palpitates, he is dazzled: “his eyes filled with tears, he said to himself: here I am, back home”.

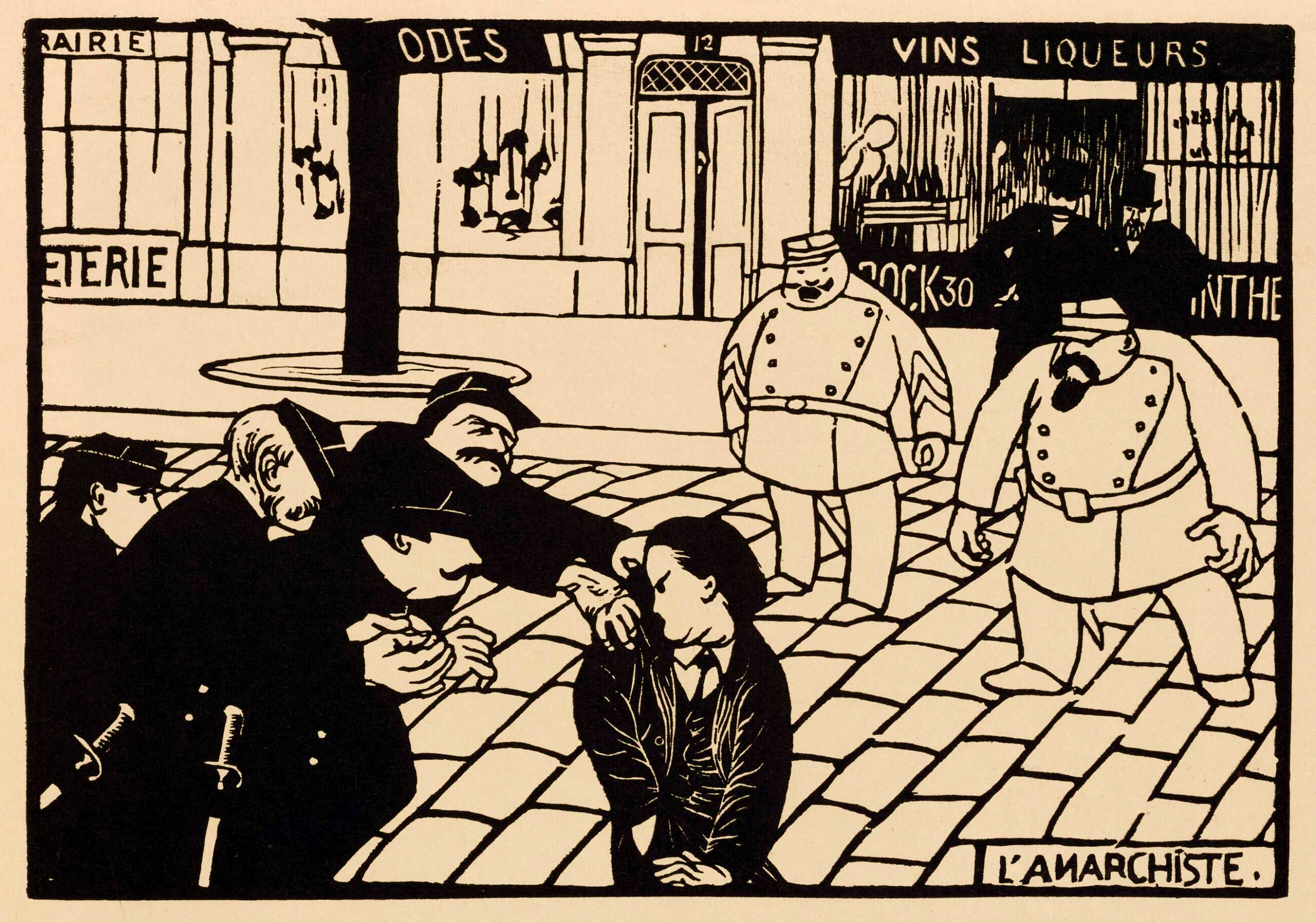

Alongside the agents of destruction, there are those of beauty and wonder, who resist chaos as much as order, the one often being only the mask of the other. If the baron’s return has such consequences, it’s because it unwittingly reveals the extraordinary vacuity of the powers that be, and the relationships of connivance and corruption that bind them together. The town mayor, the head of the gendarmerie and the members of the Local Forces (a self-proclaimed militia motorcycle gang serving Greater Hungary) are as grotesque as they are dangerous. The targeted violence of the Local Forces and the disorder they cause always prove to be in the service of municipal order, either to reinforce it or to re-establish it. And when disorder causes the councillors to waver, as in The Melancholy of Resistance it’s the army that is called in to re-establish a momentarily defeated order. It is this double game that the aberrant movements of the baron and the professor reveal in all their crudeness. Art – for there is art in the unpredictable sinuosity of their movements – cannot resist chaos without also resisting order, disturbing it, undoing it, exposing it to the disorder it conceals or uses.

Krasznahorkai loves dissonant doubles. The idiot and the scholar. There’s the baron and the professor, Janos Valsuka and György Eszter in The Melancholy of Resistance, the Prince of Genji’s grandson and Sir Wilfrod Stanley Gilmore in A Mountain to the North, a Lake to the South, Paths to the West, a River to the East. The fool marvels and wanders, the scholar knows that there is no infinity (the title of Gilmore’s live book, which the senior monk left behind when he abandoned his residence, is Infinity is a Mistake), that events follow one another without reason (everything is separate, i.e. g. all is ruin) and that all existence is governed by fear (it is at this point in his reasoning that the professor quotes Attila József: “our life is governed by fear”). This point of view is perfectly summed up by the Prince-Prophet of The Melancholy of Resistance: “He says: he is always free. He is in the midst of things. And in the midst of things he sees everything. And everything is total ruin. To his followers, he’s a prince, but to him, he’s the greatest prince. He’s the only one to see everything, to see that everything is nothing. And that’s what Prince needs… always… to know.

Partisans, they trash everything because they understand what he sees. They understand that things are deceptive, but they don’t know why. Prince, he knows that not everything exists The scientist becomes a prophet when he reveals to the world that everything is ruin, fear and finitude, and that everything else is illusion, deception and lies.

But this is only part of the truth, or rather only one perspective on the truth. The other being that there are also miracles and wonders, that sometimes the Japanese goddess Seiobo descends to earth, just as sometimes light shines through the lead of the Hungarian sky. It also happens that movement emancipates itself from order as well as disorder, that it becomes acrobatics or a solar system, that the erratic or regulated movements of the characters are arranged in an ephemeral choreography capable, as much as a masterpiece of art, of resisting the forces of chaos: halics Junior’s spectacular if (or because) drunken act from the railway maintenance department in Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming, and Janos’s performance-demonstration of the rotation of the stars and the solar eclipse in The Melancholy of Resistance, which Belá Tarr so wonderfully brought to life in The Werckmeister Harmonies. The separate ceases to be separate, the goddess becomes one with her character, the amazed becomes one with the amazed, and the infinite becomes actual.

As Stanley Gilmore writes, without daring to believe it: “infinity […] could exist in only one case, if there were two things, two elements, two particles, if there were two gods, two birds, two flower petals, if there were two sighs, two gunshots, two caresses, without anything, without any distance between them, such is the one and only case in which we could speak of infinity, if this distance did not exist.”

This choreography is also, eminently, that of Krasznahorkai’s writing. Each paragraph of the book is almost always a single sentence, often running over several pages. What does the sentence do? Several things. It makes heterogeneous perspectives coexist, holds them together, passes them seamlessly through one another, and thus equalizes and confronts them. Its power is dialogical. It reports what is said, while describing what is done and thought by the speaker, moving from “I” to “she” or “he”, from the voice to the perspective on the voice, to the body, place, person or group it addresses.

Its power is holistic. It translates complex movements, making them visible, becoming a volume, a multi-dimensional space that includes its spectators, transcribing them into rhythms of syntagms, which stretch or shrink according to the accelerations and decelerations of the moving bodies and the ratios of their respective speeds. Its power is therefore choreographic in the true sense of the word. It thinks, asserts, reasons, argues, contradicts itself, then restores the context of the elocution: how does it speak? to whom? where? from what body? picks up the thread of thought, relates an anecdote, quotes an author, insults another, and so on. Its power is idiotic and speculative. Krasznahorkai’s sentence does at least as much as it says. It constructs and makes possible the reality it represents. It makes the voices or perspectives it embodies coexist, it becomes the movement it describes, it situates what it reports or translates, it thinks at the same time as it follows the course of a thought. But, above all, it carries the reader along in its dance. A dance whose rhythm is set by the sequence of chapter headings, which must be said in the loudest voice: TRRR RAM PAM PAM PAM PAM HMMM RÁRÍRÁ RÍ ROM.

Le baron Wenckheim est de retour by László Krasznahorkai, translated from the Hungarian by Joëlle Dufeuilly, published on April 5, 2023 by Cambourakis, 528 pages.

✪