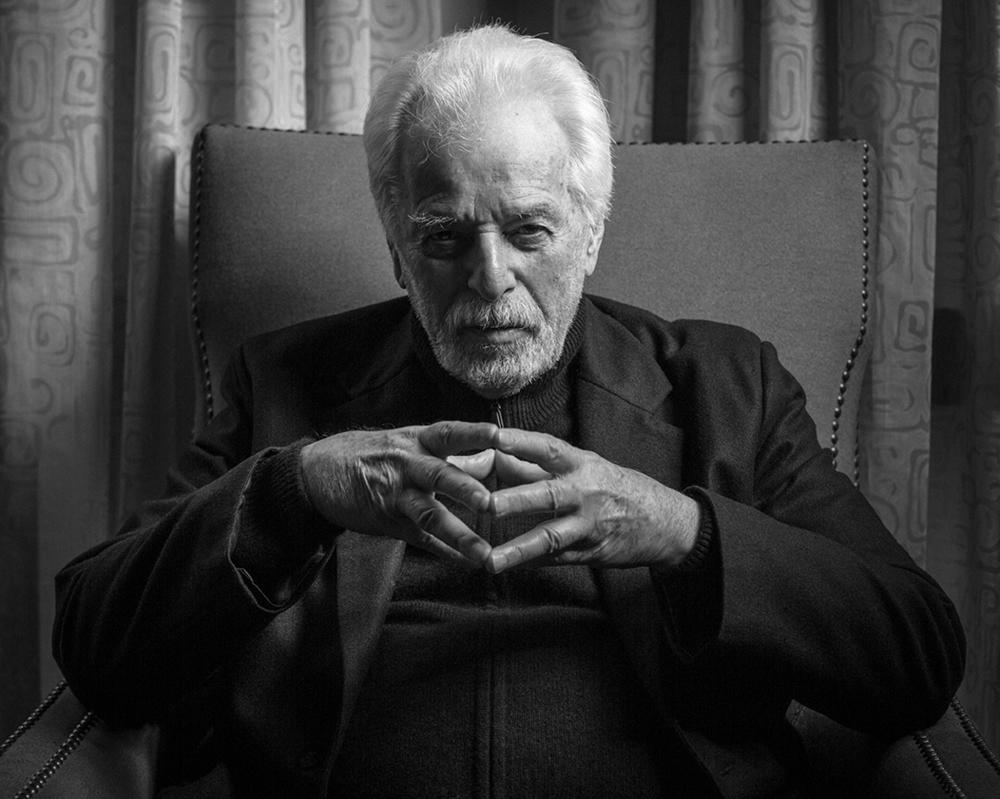

In this wildly imaginative, powerfully moving, “psychomagical” autobiography-cum-novel, Alejandro Jodorowsky tells the story of how his Ukrainian Jewish grandfather, his fiery wife, Teresa, and their four children moved to Chile under fake passports and assumed Christian identities, with only a half-kopek to their name and no idea how they’d forge their new lives.

The book is a visionary family saga filled with ancestors both mythical and real—including bee-covered relatives, women who commune with wolves, snake charmers, and militant anarchists.

Where the Bird Sings Best owes its title to Jean Cocteau’s reflection: “A bird sings best on its family tree.” Drawing on history, ancestral legends, and intimate family stories, Jodorowsky brings to bear in this deeply personal search for his roots the same unique storytelling genius evident in his iconic films.

In 1903, Teresa, my paternal grandmother, got angry. First with God and then with all the Jews of Dnepropetrovsk (in Ukraine) who still believed in Him, despite the deadly flood of the Dnieper. Her beloved son José had perished in the flood. When the house began to fill up with water, the boy pushed a chest out to the yard and climbed up on top, but it didn’t float because it was stuffed with the 37 tractates of the Talmud.

After the burial, carrying all the children she had left, four toddlers—Jaime and Benjamin, Lola and Fanny, conceived out of obligation more than passion—she ferociously invaded the synagogue with her husband hot on her heels. She interrupted the reading of Leviticus 19: “Speak to the entire assembly of Israel, and say to them—”

“I’m the one who’s going to speak to them!” she bellowed.

She crossed the area forbidden to her for being a woman and pushed aside the men who, victims of an infantile terror, covered their bearded faces with prayer shawls, silken tallits. She threw her wig to the floor, revealing a smooth skull red with rage. Smashing her rough face against the Torah parchments, she cursed at the Hebrew letters:

“Your books lie! They say that you saved the entire nation, that you parted the Red Sea as easily as I slice my carrots, and yet you did nothing for my poor José. That innocent boy was blameless. What lesson did you want to teach me? That your power has no limits? That I already knew. That you are an unfathomable mystery, that I should test my faith by simply accepting that crime? Never! That’s all well and good for prophets like Abraham. They can raise the knife to the throats of their sons, but not a poor woman like me. What right do you have to demand so much of me? I respected your commandments, I constantly thought of you, I never hurt anyone, I gave my family a holy home, I prayed as I cleaned, I allowed my head to be shaved in your Name, I loved you more than I loved my parents, and you, you ingrate, what did you do? Against the power of that death of yours, my boy was like a worm, an ant, fly excrement. You have no pity! You are a monster! You created a chosen people only to torture them! You’ve spent centuries laughing, all at our expense! Enough! A mother who’s lost hope and for that reason doesn’t fear you is talking to you: I curse you, I erase you, I sentence you to boredom! Stay on in your eternity, create and destroy universes, speak and thunder—I’m not listening anymore! Once and for all: Out of my house. You deserve only my contempt! Will you punish me? Cover me with leprosy, have me be chopped to pieces, have the dogs eat my flesh? It doesn’t matter to me. José’s death has already killed me.”

No one said a word. José wasn’t the only victim. Others had just buried family members and friends. My grandfather Alejandro, from whom I inherited part of my name, because the other half came from my mother’s father, who was also named Alejandro, dried with infinite care the tears that shone like transparent scarabs on the Hebrew letters, bowed again and again to the assembly; his face crimson, he muttered apologies that no one understood and led Teresa out, trying to help her carry the four children. But she wouldn’t let go of them and hugged them so tightly against her robust bosom that they began to howl. A hurricane wind blew in, the windows opened, and a black cloud filled the temple. It was every fly in the region fleeing a sudden downpour.

For Alejandro Levi (at that time our family name was Levi), his wife’s break with tradition was just another nasty blow. The nasty blows formed a part of his being that could not be dissolved: He’d put up with them stoically throughout his life. They were like an arm or an internal organ, a normal part of reality. He hadn’t even been three when the Hungarian maid went mad. She walked into the bedroom where he slept hugging his mother, Lea, and murdered her with an ax. The hot spurts dyed his naked little body red. Five years later, in an outburst of hatred whose source was the belief that the blood of Christian children was used to make matzo, a swarm of drunken Cossacks poured along the streets of Ekaterinoslav: They burned the village, raped women and children, and beat Jaime, his father, to a bloody pulp because he refused to spit on the Book. The Jewish community of Zlatopol took him in. They gave him a bed in the religious school. There they taught him two things: to milk cows (at dawn) and to pray (for the rest of the day). Those liters of milk were the only maternal scent of his childhood, and to get feminine caresses, he taught the ruminants to lick his naked body with their huge, hot tongues.

Reciting the verses in Hebrew was torture until he and the rabbi met in the Interworld. It happened like this: Alejandro, because he davened so much, chanting the sentences he didn’t understand, felt that his feet were freezing, that his forehead was boiling, and that his stomach was filling up with an acidic air. He was ashamed to breathe deeply with his mouth open like a fish out of water and faint right there in front of his classmates, who did understand the texts… unless their expression of intense faith was nothing more than an act put on so they could later get a good supper as a reward. He made a supreme effort, and leaving his body at its davening, he moved outside himself to find himself in a time that didn’t pass, in a not extensive space. What a discovery that refuge was! There he could vegetate in peace, doing nothing, only living. He felt intensely what it was to think without the constant threat of the flesh, without its needs, without its multiple fears and fatigues; without the contempt or pity of others. He never wanted to go back, only to remain there in an eternal ecstasy.

Piercing the wall of light, a man dressed in black like the rabbis but with Oriental eyes, yellow skin, and a beard with long, lax whiskers came to float next to him.

“You’re lucky, little man,” he said. “What happened to me won’t happen to you. When I discovered the Interworld, there was no one there to advise me. I felt as fine as you and decided not to go back. A grave error. Abandoned in a forest, my body was devoured by bears. And then, when I needed human beings again, it was impossible for me to return. I found myself condemned to wander through the ten planes of Creation without the right to stop. If you let me throw down roots in your spirit, I’ll return with you. And to show my thanks, I’ll be able to advise you—I know the Torah and the Talmud by heart—and you’ll never be alone again. What do you say?”

What do you think this orphan boy was going to say? Thirsty for love, he adopted the rabbi, who was from the Caucasus and exaggerated his study of the Kabbalah. And because he sought out the wise saints who, according to the Zohar, live in the other world, he got lost in the labyrinths of Time. In those infinite solitudes, he, a contumacious hermit, learned the value of human company, understood why dogs always thirst for the presence of their master, and discovered that others are a kind of food, that men without other men perish from spiritual hunger.

When he recovered consciousness, he was stretched out on one of the school benches. The teacher and his classmates were gathered around him, all pale because they thought he was dead. It seems his heart had stopped beating. They gave him some sweet tea with lemon and sang to celebrate the miracle of his resurrection.

Meanwhile, the rabbi was dancing around the room. No one but my grandfather could see or hear him. The joy of the disincarnate man to be once again among Jews was so great that for the first time he took control of Alejandro’s body and recited (in a hoarse voice and in Hebrew) a psalm of thankfulness to the Lord:

“Thou hast been our dwelling place in all generations.”

Everyone panicked. The boy was possessed by a dybbuk! That devil would have to be flushed from his guts! The rabbi realized his error and leaped out of my grandfather’s body. And no matter how hard Alejandro protested, trying to explain that his friend promised never again to enter his body, they went on with the spell-removal ceremony. They rubbed him down with seven different herbs, they made him swallow an infusion of cow manure, they bathed him in the Dnieper, whose waters were many degrees below zero, and then, to warm him up, they gave him a steam bath and thrashed him with nettles.

Even though they considered him cured, they still went on feeling a superstitious mistrust for a while. But my grandfather grew up, and they got used to the presence of his invisible companion. They began to consult him, first about Talmudic interpretations, then about animal illnesses, and then, seeing the good results in the first two instances, they went on to consult him about human maladies. Finally, they made him into a judge in all their conflicts. The entire village praised the rabbi’s intelligence and knowledge, but they had no regard whatsoever for Alejandro. Timid by nature and essentially humble, he had no idea how to take advantage of his situation, not even as intermediary. People invited the rabbi, not him. Whenever he came into the synagogue, they’d ask whether the rabbi had come, because from time to time the man from the Caucasus would disappear to visit other dimensions, where he’d converse with the holy spirits.

If the rabbi accompanied him, they’d seat him in the first row. If not, no one bothered to speak to him or offer him a chair. The man from the Caucasus had said that what he liked most was to see children. So whenever people came to consult him in the modest room Alejandro had next to the stable, they brought along their offspring, bathed, combed, and dressed for the Sabbath. This exhibition of children was all the pay he got. No one bothered to bring him an apple pie, a pot of stuffed fish, a bit of chopped liver. Nothing. Only the rabbi existed; my grandfather was the real invisible man. Accustomed as he was from the cradle to not being pampered, he was neither sad nor happy. He milked the cows, prayed, and at night, before sleep wiped him out, held long discussions with his friend from the Interworld.

One day, at the first light of dawn, Teresa approached him. She was small but with robust legs, imposing breasts, and a character of iron. She fixed her dark eyes, two glacial coals swimming in feverishly sunken sockets, on him and said:

“I’ve been observing you for a while. I’m of age to have children. I want you to be the father. I’m an orphan like you, but not as poor. You’ll come to live in the house my aunts left to me. To be able to feed the children, we’re going to organize the consultations. You will be paid. The rabbi needs nothing because he doesn’t exist. He’s the product of your madness. Yes, you’re crazy! But it doesn’t matter: What you’ve invented is beautiful. What you think he’s worth, that’s what you’re worth. That knowledge comes only from you. Learn to respect yourself so others will respect you. Never again will they speak with the phantom. They will tell the problem to you and have to come back later to hear the answer. They will no longer see you in a trance speaking with someone who’s invisible. I’ll set the prices, and we will not accept invitations to dinners where they try to take advantage of you. The rabbi will stay home. He will never go out on the street with you, and if he doesn’t like that, he can leave—if he can. But as soon as he leaves you, he’ll dissolve in the nothingness.”

And without awaiting an answer from Alejandro, she kissed him full on the mouth, stretched out with him under the udders of the cows, and took permanent possession of his sex. He, after gushing forth his soul in his sperm, squeezed the udders so the two of them would be bathed in a shower of hot milk. When they married, she was pregnant with José. The community accepted the new rules of the game, so never again did the family table lack for chicken soup or fried potatoes or a fresh cauliflower or a plate of porridge. Ten months after José’s birth, they had twin boys. The year after that, twin girls.

In the corset shop, in the presence of her neighbor ladies, Teresa would brag about living with a holy husband who never stopped praying, even during his five hours of sleep. Moreover, he would always eat, no matter what the dish happened to be, with the same rhythm so he could chew without ceasing to recite the psalms. And when he wasn’t praying, he knew only how to say two words: “Thank you.”

[dropcap size=big]E[/dropcap]verything was going so well and then, catastrophe! José dead! An extraordinary son, good among the good, obedient, well mannered, clean, with an angelic voice for singing in Yiddish, of resplendent beauty. Yes, his natural joyfulness brightened sorrows; he was a dash of salt in the tasteless soup of life, a shower of colors for the gray world. Whenever he strolled past the trees at night, the sleeping birds would awaken and start to sing as if it were daybreak. He was born smiling, he drew up blessing anyone whose path he crossed, he never complained or criticized, he was the best student at the yeshiva. Why did a ray of sunshine have to die?

Teresa clung violently to her grief. Forgetting it, she thought, would be a betrayal. She refused to accept that the deceased was buried, and she held him there, swallowing muddy water, blue from asphyxiation, an incessant victim, a lamb in eternal agony. This she did to justify her hatred not only of God and her community but also of the river, the plants, the animals, the dirt, Russia, all of humanity. She forbade my grandfather from solving the problems of others and demanded—otherwise she would kill herself—that he never again mention the rabbi.

They sold the little they had and went to live in Odessa. There they were taken in by Fiera Seca, Teresa’s sister, who was two years younger. Their father, my great-grandfather, had been married to three women and was a widower three times. All his wives died giving birth the first time, and the children in turn never lasted more than three days in the cradle. According to the old gossips, Death was in love with him and out of jealousy snatched away the wives and their fruit.

Abraham Groisman was a strong, tall man with a curly red beard and big green eyes. He made a living through apiculture. And if all that stuff about Death’s being in love with him was a tale told by superstitious witch doctors, his love for his bees was a clear fact. Whenever he went to harvest the honey from the hundred or so little multicolored hives, the bees would cover him from head to foot without ever stinging him. Then they would follow him like a docile cloud to the shed where he bottled the delicious honey, and many nights, especially during the glacial winters, they would gather on his bed to form a dark, warm, and vibrant blanket.

Teresa’s mother, Raquel, had been 13 when she gave birth in the cemetery. The old crones put her in a grave and wrapped her in seven sheets so Death wouldn’t see the baby. There, in the cool earth, surrounded by dark bones, my grandmother bore her first child, whose mouth was quickly filled with a fragrant nipple to maintain the silence that was essential: Death had a thousand ears! Abraham, convinced that once again he was going to lose mother and child, prepared his heart for the tragedy by repressing any feeling. The survival of those two beings wouldn’t generate either heat or cold. He just went on submerged in his sea of bees, speaking with them in an inaccessible universe. But when Raquel, now 15, became pregnant once again, hope blazed in his soul.

Despite the fact that he’d been warned that the Black Lady, as faithful and loving as the bees, would follow him no matter where he went, he went to the cemetery, pushing aside the ladies who were holding up the seven roofs of sheet, and looked toward the deep grave. He saw exit the bloody temple the most beautiful of girls. A strange wind whipped the white cloth and carried the sheets toward the mountains as if they were immense doves.

The mother began to die. “Fool!” the women shouted. “Why did you come? You’ve brought your ferocious lover. She’s already devouring the mother. The daughter is next.” They poured salt and vinegar over the child’s head and baptized her with a name that would shock and disgust Death himself: Fiera Seca. Then they put her in a basket, swaddling her in clusters of grapes, and carried her off to a secret place the father could never know in order to hide her from the Enemy. Fiera Seca had to live as a prisoner in a barn until she was 13, when her periods began. When her childhood ended, the danger disappeared. Death was looking for a girl, not a woman. Fiera Seca came home, led by one of the old gossips. As she walked along the streets, the terrified townspeople closed doors and windows. To scare off Death, in case she discovered the child’s hiding place, they’d taught Fiera Seca to make horrible faces one after another. Her face, like a soft mask, passed from one ugliness to another. If you looked at her for more than ten seconds, you got a headache.

When Fiera Seca entered the room, which was simultaneously kitchen, dining room, and bedroom, Teresa ran out to the garden along with the dogs, which began to howl, and the cats, which began to hiss. Fiera Seca was all alone. She heard footsteps. It had to be Death! Outside her hiding place she felt more vulnerable than ever. Aside from contorting her face, she’d also begun to deform her body. She bowed her legs, twisted her spine, and made her hands look like claws. She drooled and foamed at the mouth, tinting that disgusting mess with blood she sucked out of her gums. The door opened with an insect-like screech. Abraham saw a monster, a species of enormous spider, but he did not flee because he was covered with bees. To Fiera Seca, the buzzing of that dark mass seemed like the song of the Black Lady.

There they stood, face to face, sweating in terror. Perhaps the only beings that understood the situation were the bees. They began to fly in a circle that became larger and larger until it surrounded father and daughter. Within that living cordon, the girl saw the most beautiful man she’d ever been able to imagine. In the depth of his green eyes, she found an ocean of goodness. That sublime spirit became a world where, if she could make herself small, she would have wanted to live. Little by little, she ceased making faces and stretched out her body, revealing what she was—a beautiful woman. Abraham realized that all the others, those who died giving birth, had been nothing more than sketches of the thing that, without knowing it, he’d sought forever: Standing erect before him, like a tremendous miracle, his soul was calling him. They submerged one into the other, they spoke words of love to each other, they wept, laughed, sang, and fell into the bed. The bees formed a curtain that separated them from the world, and there they remained, two bodies transformed into a single bonfire, not thinking of the consequences.

Teresa felt she was superfluous. Her father and sister disappeared forever, transformed into lovers. She put what little she had in a sack and went to live with her aunts. Two years later, she received news from her sister, a letter:

Forgive me, Teresa, for having forgotten you all this time. Dad is dead. You are the only one who knew about our secret. I hope you’ll understand. It was stronger than we were, a passion we couldn’t control. No one in the neighborhood dared to imagine anything like that. Whenever I went out to shop, I made my faces and contortions so that no one would speak to me. My father, my lover, only showed himself covered with bees. Our real bodies were a miracle we enjoyed in the intimacy of the house. To avoid spies, Abraham taught the insects to rest on the roof and exterior walls of the house until they covered it with a thick quilt. We made love inside a gigantic honeycomb, drunk on pleasure, unable to stop, again and again, wishing we could fuse and become one single being. That insatiable hunt, that impossible dissolution, mixed in with the pleasure a constant pain, a dagger piercing our collar of orgasms. A short time ago, I became pregnant. We thought we were angels, beings from another world, unaffected by human phenomena: We had to return to reality. After five months, my stomach began to bulge. In dreams, Abraham received a visit from the Black Lady. She was insane with fury and jealousy. When he awakened, he said, “I am going to cause your death. She will not listen to my pleas. Her cruelty knows no limits. You will never be able to give birth and live. Understand me, my daughter, my wife, I must sacrifice myself, hand myself over to Death, let her carry me off to her palace of ice. That way her love will be satisfied, and she will not devour you.”

I wept for days, but I could not convince him that it was I who should disappear. He filled a bathtub with honey and submerged in the golden syrup. He died looking at me. He never closed his eyes. A tranquil suicide—he was smiling, and the bees flew, forming a crown that slowly circled over the yellow surface. Under the mattress, I found a note: “I shall never stop loving you. Please, look after the bees. Don’t abandon them. They are my memory.”

I fell into the bed. I spread my legs, and as my stomach shrank I expelled an interminable sigh from my sex. Nothing remained of our child. It turned into air.

Teresa never answered that letter and never returned to the paternal home until the day she went to live in Odessa with Alejandro and the four children. An obscure shape came out to meet them. When they walked into the room, the bees separated from Fiera Seca and went to suck at little plates filled with sugared juices. Screaming, Fiera Seca threw herself into Teresa’s muscular arms. She did not seem to notice the presence of my grandfather and the children.

“Oh, sister! No one knows about Abraham’s death. I still make the atrocious faces when I go shopping, and I receive those who come here to buy honey covered with insects, so they go on thinking it’s Abraham. I never buried our father.”

And as the family was moving in, she led Teresa to the barn. Among the honeycombs, from which came a buzzing similar to a requiem, was the bathtub filled with honey with the smiling corpse beneath its yellow surface.

“Honey is sacred, sister. It preserves flesh eternally. He’s never wanted to leave. I feel him stuck to me. He’s waiting for me.”

As she said that, Fiera Seca took off her clothes. Soon she revealed her naked body: a delicate structure with a skin so fine that through it could be seen the tree-like pattern of the veins. A thick, animal-like pubis contrasted with that angelic delicacy: It was so black it emitted blue sparkles and covered her belly up to her navel.

“I shouldn’t abandon the bees. They are the reason I remained in this world. That’s what he asked me to do. But now you’ve come, and I can leave. I’m leaving these wise animals in your care. If you look after them carefully, they will feed your whole family.”

And with no further explanations, she leaped into the tub, embraced her father, and allowed the honey to cover her. She made no signs of drowning and seemed neither to suffer nor to die. She simply became forever immobile; her eyes wide-open, staring into the open eyes of the other cadaver.

Teresa felt as dead as her father or her sister. Only her obligation to her family kept her alive. And hate as well. Especially hate. It was a source of energy that allowed her to put up with the world only so she could curse it. In all things she saw the presence of a cruel, despicable God. There was nothing that didn’t seem absurd, impermanent, or unnecessary to her. The plot line of life was pain. She could detect the incessant fear hidden in laughter, in moments of pleasure, in the stupid innocence of children.

For her, the world was a prison, a charnel house, the sick dream of the monstrous Creator. But what annoyed her most (a rage that caused her to curse from the moment she awoke until the moment she fell asleep) was knowing, without wanting to confess it to herself, that this hate disguised an excess of love. During childhood she learned to adore God above all things, and now, in her absolute disillusionment, she had no idea what to do with that immense feeling. Fervent oceans she could not channel toward her husband or children because they were condemned to die prematurely.

In the same way the Dnieper had flooded its bank and carried José away, some accident or other would exterminate them. Security was fragile. Nothing lasted. Everything shrank to nothing. Unthinkable evils were possible. A rock could fall from the sky and smash her family; an ant could lay eggs inside their ears, where armies of tiny beasts would be born that would devour their brains; a sea of fetid mud flooding down the mountainside could cover the city; mad hens could become carnivores and peck out the eyes of children; anything could happen.

What was to be done with that ownerless love building up in her bosom, shaking her heart so violently that its pounding could be heard in the night up and down the street, drowning out the chorus of snores? Suddenly, without her being able to understand why, she discovered the only thing deserving her love in this world: fleas! She remembered a circus act she’d seen in her childhood and decided to train those insects. She always carried out her tasks as wife and mother. She provided her family with a clean home, she cooked and ironed, all the while proffering insults. Before her four children went to bed, she made them get down on their knees and recite: “God does not exist; God is not good. All that awaits us is the cat who will urinate on our grave.” And when they slept under the huge eiderdown next to the brick stove, she, hidden in the cold basement, dedicated herself to domesticating her fleas.

When she had fled her father’s house, Teresa stole his pocket watch, the only souvenir of him she wanted to keep. Now she emptied it of its machinery, removed the white circle of the dial with its Roman numerals and hands like women’s legs, and within the case, its cover pierced with holes so they could get the necessary oxygen, she housed her pupils. There were seven of them. To each she gave a different territory to suck blood: her wrists, behind her knees, her breasts, and her navel. She bought a magnifying glass and other necessary instruments and made them costumes, decorations, tiny objects, furniture, and vehicles. She reduced her sleep time and spent entire nights teaching them to jump through hoops, to fire a miniature cannon, to play drums, to swing, to play ball. Little by little she got to know them. They had different personalities, subtly different bodies, individual forms of intelligence. She named them. She had better communication with them than she’d had with dogs. The link was profound. After a long while, she could speak and plot with the fleas against God.

Translated from the Spanish by Alfred MacAdam. Where the Bird Sings Best is published by Restless Books. ✪

![[Futuristika!]](https://futuristika.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/futuristika-logo.png)