Known for his cartoons, collages and illustrations, Hoffmeister was also a journalist, editor, writer and diplomat. Throughout his life, Hoffmeister constantly brought together linear arts with written and political language, discussing social, cultural and political events with humor and irony.

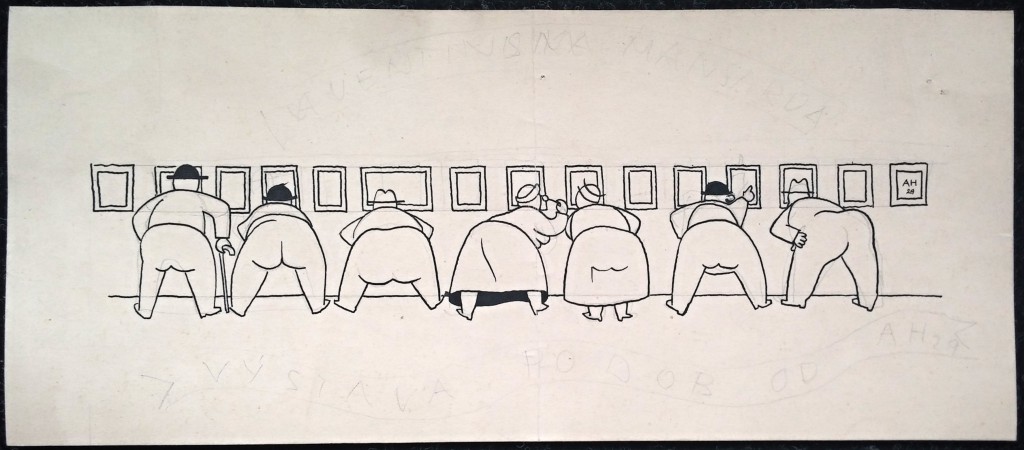

In his cartoons and illustrations, his opposition to fascism was especially evident. In the 1930s, he founded the anti-fascist humor magazine Simplicus in Prague, combining line with political resistance. The 36-portrait set in the Graphic Arts Collection (including figures such as Hitler, Jean Cocteau, James Joyce, and Pasternak) bears traces of both individual analysis and period criticism in his portraits. With a simple, almost stenographic style, he reflected the characters and the atmosphere of the period, using techniques of exaggeration and distortion to emphasize the human side of social figures rather than idealizing them.

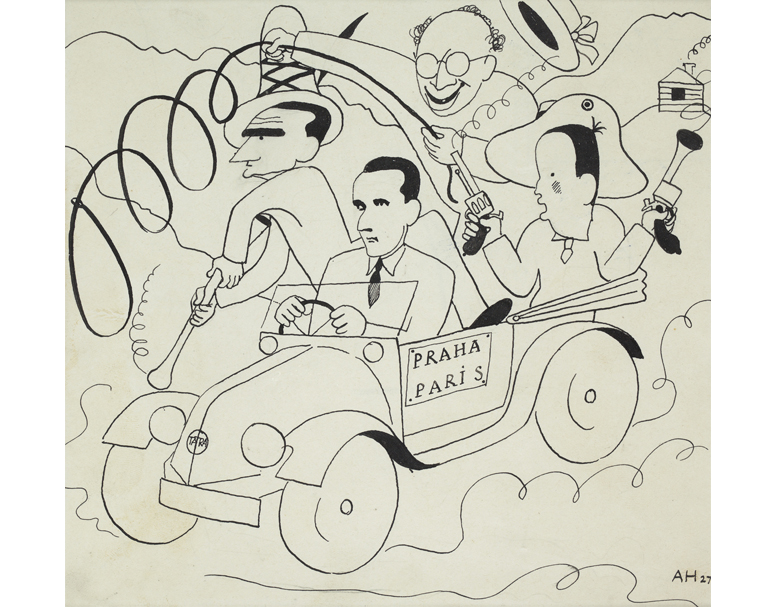

Hoffmeister’s political and literary identity is integrated with his art. He edited major publications for years and created multi-layered narratives by intertwining drawing and words in his texts. Especially during the rise of Nazi Germany, he brought together political irony and opposition through art in his magazine Simplicus. During his exile, while fleeing the war, he opened cartoon exhibitions in centers such as France, Morocco, the USA and London, and drew political cartoons for the New York Times Magazine. He wrote the libretto for the children’s opera Brundibar, intertwining artistic sensitivity with social trauma and struggle.

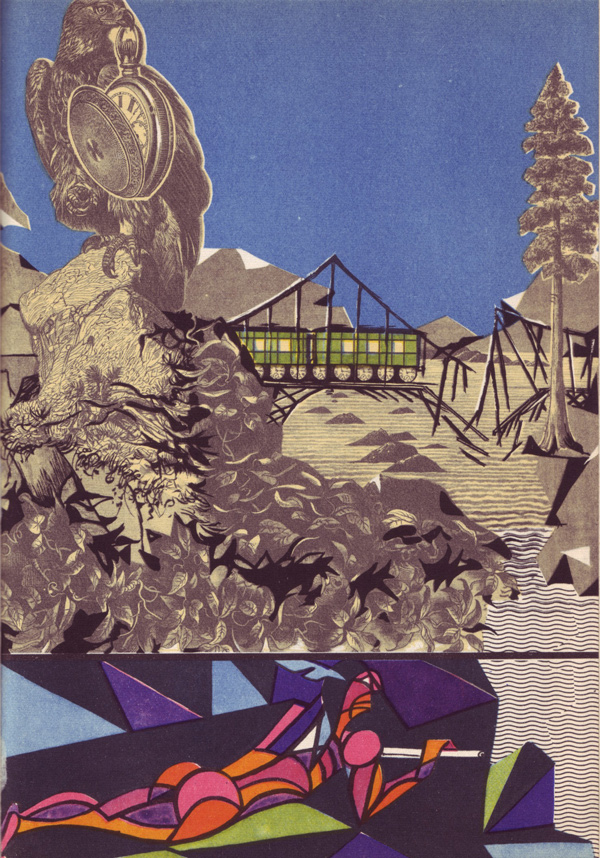

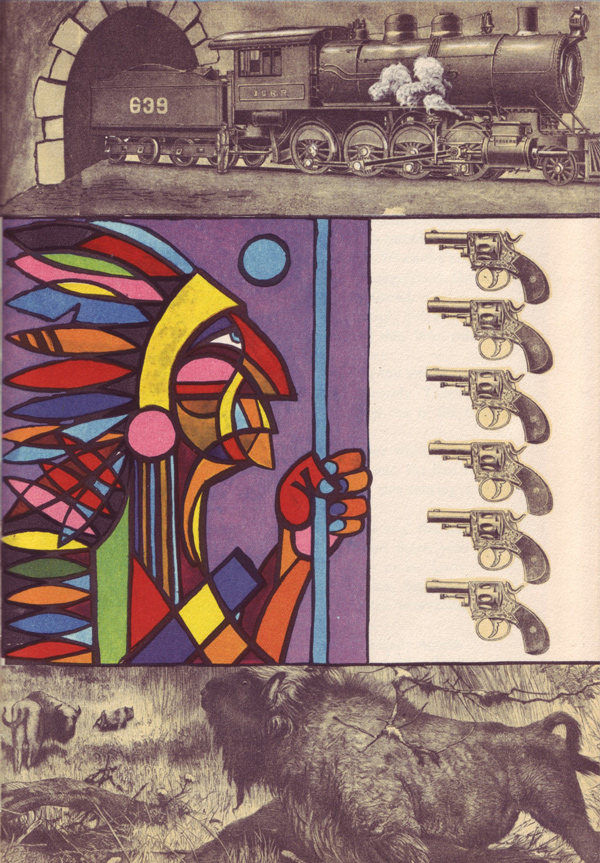

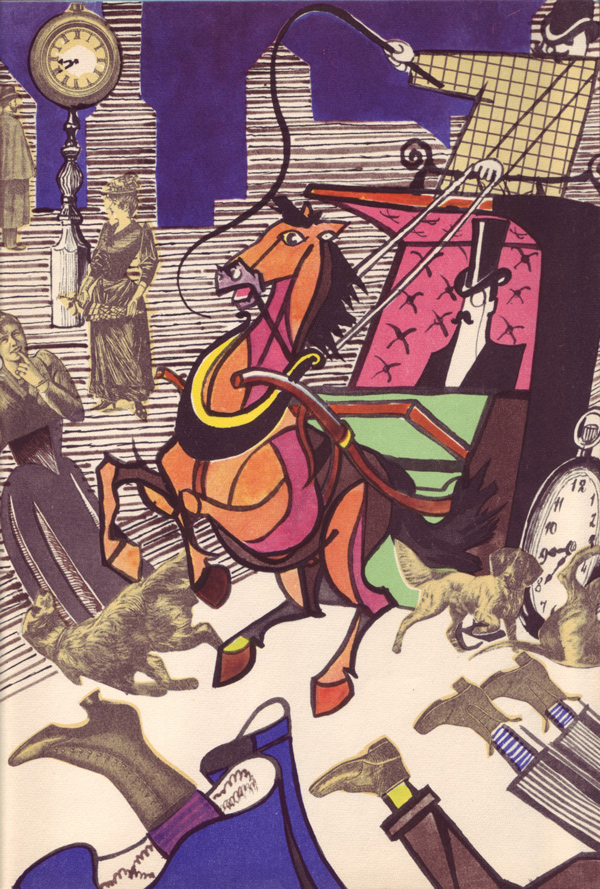

Hoffmeister’s art was not limited to the line; surrealist influences are noticeable in his collages and illustrations. Especially in his pre-war works, it is possible to see poetism and surrealism side by side. He combines line with poetry and self-portrait with narrative technique. Hoffmeister, who believed that a drawing could be “poetry, telegram and architectural work at the same time”, produced his works with a creative approach that transcended the boundaries between disciplines. Simplicity, economy and clarity stand out in his drawings; physiognomic features are emphasized in his portraits, which are stripped of unnecessary details. In his collages, he opened the door to surrealism by disrupting the usual order of objects; in his drawings, he applied the principles of the surrealist movement with absurd, unconscious motifs. His contact with the surrealists was not only aesthetic but also deep on a personal level. Hoffmeister personally met surrealists such as Louis Aragon, Philippe Soupault and Tristan Tzara in Prague and on his travels, painted their portraits and took part in collective exhibitions.

In addition, he was a representative in international events; he contributed to the art world with art and cultural organizations after his assignments as UNESCO and Ambassador to Paris. He opened exhibitions in centers such as London, Paris, Mannheim and Venice Biennale; in his portraits, he created vivid and ironic images of his contemporaries such as Picasso, Dali and Joyce. Hoffmeister, who offered social criticism with his pen as well as with his words, and disrupted the context with humor and irony, was remembered by his contemporaries as “one of the most famous portraitists of our time”.

Adolf Hoffmeister’s art and multifaceted production represented a unique combination of social resistance, literary intelligence and surrealist aesthetics. The political consciousness in his cartoons and illustrations, the deep unity of literature and line, and his dialog with the surrealists brought his art into a universal atmosphere of surrealism. Hoffmeister thus attained a respected position among artists at the intersection of modernism, social criticism and surrealism. With his political identity, Hoffmeister became an important figure in the use of art as a medium of resistance and criticism. In his relations with the surrealists, he believed in the politically transformative potential of art and combined both literary and visual narratives in his experimental, boundary-crossing approaches. The images and lines he used in his poetry reflected human irony as much as his political stance.

✪

![[Futuristika!]](https://futuristika.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/futuristika-logo.png)