To move MacGowan beyond the cliché of the “drunken Irish bard” is to recognize him as the creator of a political poetics: a collision between punk ethos and the fragility of Irish migrant history. His music made “rebellion” more than just a musical posture; it became a historical wound inscribed onto the migrant body, and the translation of that wound into song. His stance was less about the nihilism often associated with punk, and more about a poetics of survival, about keeping political memory alive.

MacGowan’s life recalls Edward Said’s notion of the “experience of displacement”: a figure belonging fully nowhere, trapped between two cultures. To be Irish in England under Thatcher meant carrying the stigma of postcolonial identity. During The Troubles, Irishness itself became politically suspicious. The anger in MacGowan’s songs echoes not only class poverty but also cultural exclusion. The Pogues’ “folk-punk” was precisely the aesthetic of in-betweenness: clinging to roots while defiantly performing those roots in a place where they were continually degraded and criminalized.

MacGowan first entered the stage bloodied at a Clash concert. From then on, he took punk’s speed and fury but refused to replicate it wholesale. His difference was to infuse the stream-of-consciousness of Joyce, the drunken wit of Brendan Behan, and the lyricism of pub ballads with punk energy. In albums like Rum, Sodomy & the Lash or in tracks such as “A Pair of Brown Eyes,” the nakedness of working-class misery, the debris of history, and a mocking laugh all coexist. It was the transformation of punk’s annihilation into an elegy that kept memory alive.

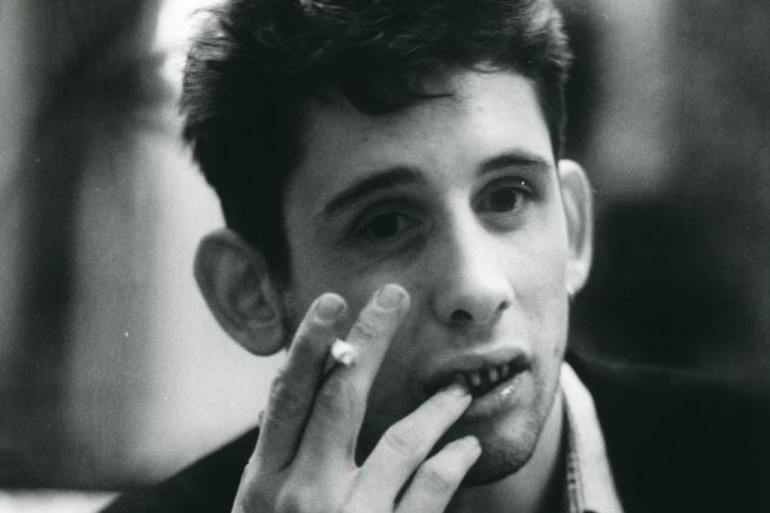

His decaying, disheveled body could itself be read as a manifesto. On stage — the toothless mouth, the drunken sway, the difficulty remaining upright — he staged an anti-aesthetic against the sterile norms of culture. From Judith Butler’s perspective on performativity, MacGowan disrupted normative bodily performance, staging another kind of truth entirely. In this sense, he cursed the system not only through his music but through his very body.

Punk Meets Memory

MacGowan’s originality lay precisely in bringing punk and memory together. The Pogues’ folk instruments were never just exotic touches; they reactivated the fragments of an exiled identity by attaching them to punk velocity. The stance recalls Walter Benjamin’s “angel of history”: The Pogues’ songs were the angel’s melody, running forward while carrying the debris of the past on its back. Drunken joy and elegy, the cry of freedom and the melancholy of exile, sounded at once.

Pogues concerts re-produced the festive community culture born in pubs. Anger, loneliness, and exclusion were transfigured into collective presence. Georges Bataille’s notion of “community through excess” was enacted on stage: MacGowan destroyed himself to create a bond, holding others together through his own ruins.

MacGowan’s legacy is not limited to being a “folk-punk pioneer.” He was the stage echo of modern European counter-literature: Rimbaud’s aesthetics of misery, Burroughs’ urban obsessions, Joyce’s fragmented worlds. He should be remembered as a cultural insurgent who surpassed punk’s nihilistic void, blending migrant memory, class rage, and black comedy into a poetic force.

Shane MacGowan’s songs are a ritual of memory: at once a scream, a lament, and a laugh. This is what redefined punk: not the destruction of rules, but their transformation into a drunken song of survival sung among ruins.

Influence on Underground Punk Generations

The path carved by MacGowan in punk led not only to mainstream acts like The Libertines but, more importantly, to the underground. From the late 1990s onward, crust punk, folkcore, and anarcho-punk scenes carried The Pogues’ resonance. Songs infused with alcohol, exile, the street, irony, and tragedy echoed the trail he blazed. From the squats of Berlin to DIY collectives in Italy, many bands took inspiration from The Pogues to merge folk melody with street revolt. This was not simply a musical influence but a political-poetic model that shaped the underground’s practices of “creating its own memory.”

Walter Benjamin’s conception of history resonates through MacGowan’s songs: the debris of history carried into melody. Pogues tracks become “allegories,” where past suffering (exile, poverty, violence) coexists with festive sound. Benjamin’s angel of history — staring back at ruins while propelled forward — perfectly describes The Pogues’ music: punk in motion, weighed down by the wreckage it refuses to abandon.

MacGowan’s practice was also a radical deviation from the standardized forms of the “culture industry.” Against polished pop iconography, he set a rotten body and an unrefined voice — a living example of what Adorno considered “negative aesthetics.” His ballads affirm that aesthetics must never betray truth: not beautified suffering, but raw reality transformed into a bruised kind of poetics.

This is the heritage underground punk found in MacGowan: misery not only as downfall, but as resistance. In the second and third waves of punk, particularly in anarchist circles, his lyricism functioned as a form of “negative hope.” The laughter in chaos, as Benjamin suggested, no longer promises comfort — yet hope emerges only from wreckage. MacGowan’s songs, in their insistence on this persistence in ruins, became a vital source of energy for underground punk generations. ✪

![[Futuristika!]](https://futuristika.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/futuristika-logo.png)