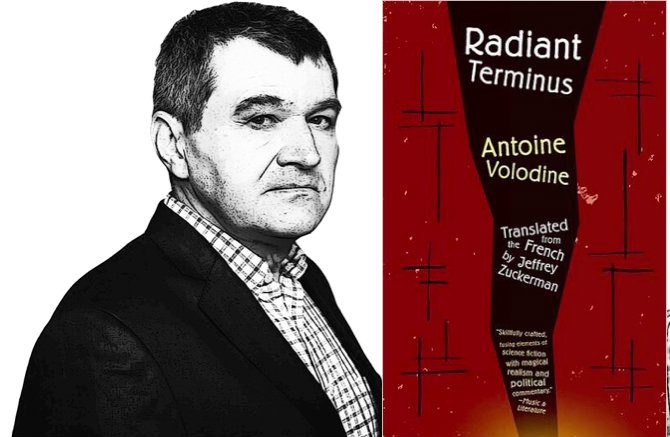

The most patently sci-fi work of Antoine Volodine’s to be translated into English, Radiant Terminus takes place in a Tarkovskian landscape after the fall of the Second Soviet Union. Most of humanity has been destroyed thanks to a number of nuclear meltdowns, but a few communes remain, including one run by Solovyei, a psychotic father with the ability to invade people’s dreams—including those of his daughters—and torment them for thousands of years.

When a group of damaged individuals seek safety from this nuclear winter in Solovyei’s commune, a plot develops to overthrow him, end his reign of mental abuse, and restore humanity.

Fantastical, unsettling, and occasionally funny, Radiant Terminus is a key entry in Volodine’s epic literary project that—with its broad landscape, ambitious vision, and interlocking characters and ideas—calls to mind the best of David Mitchell.

Translated from the French by Jeffrey Zuckerman

An Excerpt:

Kronauer opened his eyes again. The larches kept tilting, but he forced himself not to pay attention.

—So there’s a village past the trees? he asked.

—What? the young woman said, her eyes still shut.

—A village, past the trees. Is there one?

—Yes. A kolkhoz. The Levanidovo.

—Is it far? Kronauer asked.

The woman made a vague gesture. Her hand didn’t indicate direction or distance.

—I need to go there, Kronauer said.

—It’s not far, only you have to go through the old forest, the woman warned.

She paused, and then went on:

—Swamps, she said. Anthills as tall as houses. Fallen trees everywhere. Hanging moss. No trails.

Her eyes had just opened partway. Kronauer met her gaze: two brown stones, intelligent, mistrustful. Her eyelids were a bit slanted. In this face that exhaustion had made ugly with bits of earth, framed by dirty hair, her eyes were where beauty was distilled.

She could sense Kronauer’s interest in her, and, because she didn’t want any complicity between the two of them, she quickly focused on a point behind him. An abrasion on a trunk.

—If you don’t know the way, you’ll get lost, she said.

—And you? Do you know the way? Kronauer asked.

—Sure, she said quickly. I live there. My husband is a tractor driver in the kolkhoz.

—If you go back to the village, we can go there together, Kronauer said. That way I wouldn’t get lost.

—I can’t walk, she said. I’m in no state. I had a bout.

—A bout of what? Kronauer asked.

The woman didn’t reply for a minute. Then she took a heavy breath.

—And you, who are you? she asked.

—Kronauer. I was in the Red Army.

—From the Orbise?

—Yeah. It collapsed. The fascists won. We tried to fight for as long as we could, but it’s over.

—The Orbise fell?

—Yes. You know it did. They had been closing in on us for years. We were the last holdouts. Now there’s nothing left. It was a complete slaughter. Don’t tell me you didn’t hear about that here.

—We’re isolated. There’s no radio be–cause of the radiation. We’re cut off from the rest of the world.

—Still, said Kronauer. The end of the Orbise. The massacres. The end of our own. How didn’t you hear about it?

—We live in another world, said the woman. The Levanidovo is another world.

•

There was silence. The water Kronauer had swallowed gurgled in his stomach and, in the quietness that prevailed around them, he felt ashamed. He made himself talk to cover up the noise.

—You could be my guide, he said hastily.

The woman didn’t reply. Kronauer had the feeling that his body would make more rumbling noises. In order to cover up his entrails’ obscene hymn, he spouted off several useless sentences.

—I don’t want to get lost. You said there are swamps and no trails. I don’t want to find myself all alone in there. With you, it won’t be like that.

He said that with a great effort, and the woman quickly realized that he was hiding something. His words rang false. He was putting up a front. She was starting to be afraid of him again, as a male, as a rough-hewn soldier guided by bad intentions, who might be violent, who might have sordid sexual needs, who might murder sordidly.

—I can’t walk, anyway, she reminded him.

—I could carry you on my back, Kronauer suggested.

—Don’t try to hurt me, she warned. I’m the daughter of Solovyei, the president of the kolkhoz. If you hurt me, he will follow you. He will come into your dreams, behind your dreams, and into your death. Even when you’re dead you won’t escape him.

—Why would I hurt you? Kronauer protested.

—He has that power, the woman said insistently. He has great powers. It will be horrible for you, and it will last for a thousand or two thousand years if he wants, or even longer. You will never see the end.

Once again, Kronauer plunged quickly into her gaze. Her eyes expressed indignation, an anguished indignation. He shook his head, shocked that she might be afraid of him.

—Don’t hurt me, she repeated sharply.

—I’m going to carry you on my back, that’s all, Kronauer said. You’ll show me the way and I’ll carry you to the Levanidovo. That’s all. There’s no ill will here.

They stayed frozen for a minute, both of them, unsure what movement to make to begin the next episode.

—You wonder why you will hurt me? Solovyei’s daughter said. Well, there’s really no point asking. All men try to hurt women. That’s their specialty.

—Not mine, Kronauer said defensively.

—That’s their reason for being on earth, said Solovyei’s daughter philosophically. Whether they want to or not, that’s what they do. They say it’s natural. They can’t restrain themselves. And they call that love. ✪

![[Futuristika!]](https://futuristika.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/futuristika.png)