The Cremator is Juraj Herz’s unsettling 1968 effort about a deeply macabre man who slowly becomes a monster. The film has been enjoying somewhat of a revival of late, having been screened at a number of festivals, and even though it is now nearly forty years old, it has lost little of its power to chill.

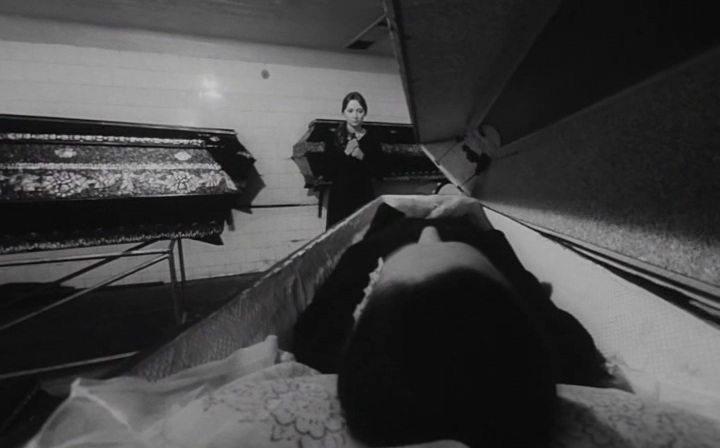

Based on a novel by Ladislav Fuks, the film is set in Prague during the Nazi occupation, and follows Karl Kopfrkingl (Rudolf Hrusinsky), a man who works in a massive, ornate crematorium. Kopfrkingl is obsessed with his work, believing death to be a release from the suffering of life, and that by incinerating corpses he is in fact liberating souls. The coming of the Nazis pushes his eccentricity into madness, perverting his already twisted ambitions and offering him the opportunity to live out his fantasies in horrifying fashion. Kopfrkingl takes to the Nazi ideal with frightening ease, gradually perverting his own beliefs as he comes to view himself as a saviour of mankind, at great cost to those around him, particularly his family.

“The Cremator” is not a horror film in the traditional sense, but is a darkly ironic and bleakly satirical comedy. Although there is little in the way of laughs, it is grotesquely humorous throughout, mainly through the lead character’s unfailing preoccupation with death. Particularly funny are his visions of the Dalai Lama, and his self-serving justifications for his own moral degeneration. Herz also plays some of the supporting cast for comedy, including a couple who turn up several times during scenes of death or violence, only to comment that they are too horrible to watch and run away. Despite such ludicrous undertones, the film is bleak and sombre throughout, with a stately pace that aptly resembles that of a funerary march.

The film is held together by Rudolf Hrusinsky’s excellent performance in the lead role, for which he deservedly received an award for best actor at the 1972 Stiges Film Festival. He exudes a quiet monstrousness, from his initially harmless and amusing morbidity, to the violent psychosis which he succumbs to during the latter stages of the film. His gradual and indeed horribly logical development into a fiend is wholly believable, and as such the film works wonderfully as a bleak character study and an insight into the mind of a man who would go on to commit atrocities through a deranged sense of compassion.

Herz’s direction has an expressionist feel, shot in black and white with a striking use of shadow and marked gothic sensibility. The film is very much seen through Kopfrkingl’s eyes, and as such, the city is given the look of a tomb, with the crematorium resembling the grand temple of death which he imagines it to be. This does mean that the proceedings do at times slip into the realm of the surreal, though this is skilfully done and works well as a method of illustrating both the character and the country’s decent into madness, giving the atmosphere that of an inescapable nightmare.

“The Cremator” is a unique example of modern gothic cinema, being both fantastic and grimly realistic. Finding comedy in the darkest recesses of the human spirit, Herz has produced a film which is genuinely chilling and filled with a sense of ominous dread. As such, it is horror of the purest kind, and is a sinister gem which deserves rediscovery. (James Mudge, beyondhollywood.com)

The films of the Czech New Wave are simultaneously accessible, experimental, and incisive — from the devastating Closely Watched Trains, to the formal freakout and confrontational sexual politics of Daisies, to the pop art satire of Who Wants To Kill Jessie?.

The Cremator is a deeply disturbing film that examines how and why people accede to totalitarianism and genocide, a topic that unfortunately is as timely now as it was in 1968. The film tells the tale of Roman, a family man who runs a crematorium in the late 1930s. Despite his Austrian heritage, Roman fancies himself a Czech man of culture and refinement; he is captivated by classical music and treasures his copy of a book about Tibetan Buddhism. At heart, however, Roman is an entrepreneur and a sycophant, preoccupied with his station in society and how he is viewed by his neighbors. Obsessed with cleanliness, he goes to the doctor for a physical following each visit to a brothel, but, tellingly, lies to the doctor and claims he has been faithful to his wife. As the Nazis begin to take power, the cremator reevaluates his relationship with all that he claimed to hold near and dear to his heart — not least of all his half-Jewish wife and quarter-Jewish children. Soon the inconceivable becomes reality, as the cremator commits abominable acts and rationalizes them through a wilfull misreading of Buddhist tenets.

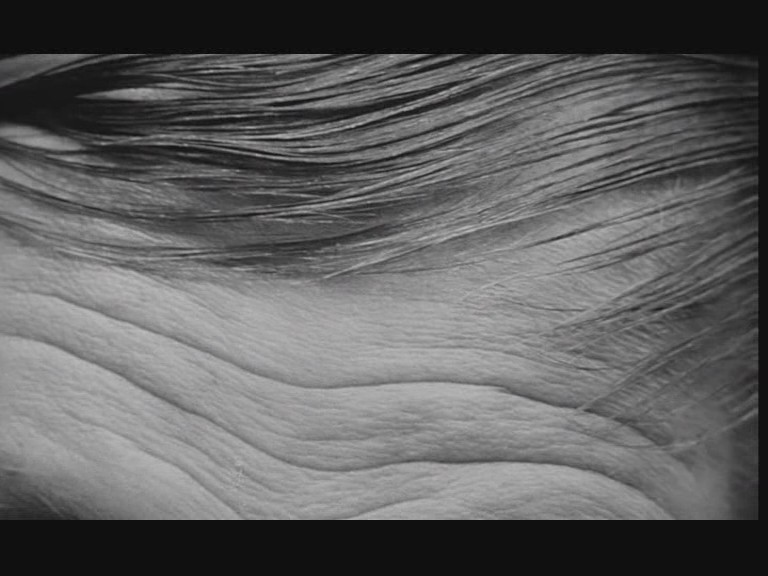

Director Juraj Herz employs the visual vocabulary of horror films and German Expressionism — chiaroscuro lighting, spectral figures, double exposures, etc. (The resemblance of lead actor Rudolf Hrusínský to Peter Lorre can hardly be considered a coincidence.) Notwithstanding these obvious influences, Herz’s images have a look all their own, alternating between distorted, funhouse-mirror closeups and breathtaking, meticulously composed wide-angle shots.

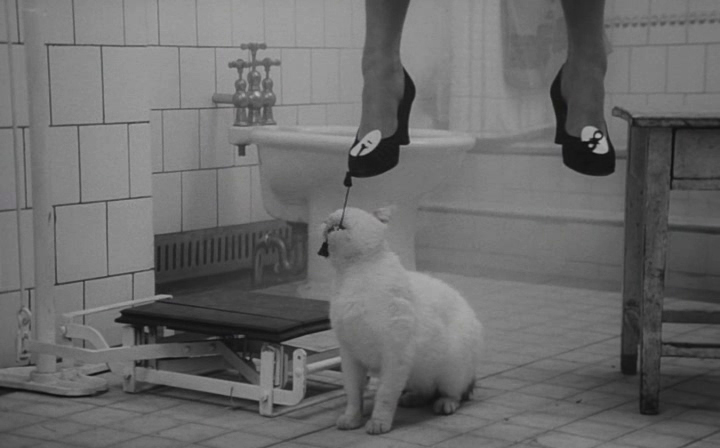

However, the film’s rapid, intentionally jarring editing rhythms are more akin to Sergei Eisenstein than Mario Bava. Herz uses montage techniques throughout the film, most obviously when he inserts shots of classical artwork that comment on the narrative. To further jar the audience, Herz also regularly inserts quasi-abstract, extreme closeups of various character’s body parts. In tandem, the creepy imagery and unusual editing keep the viewer deeply unsettled at all times.

Herz is also adept at filling each scene with telling little details. For example, the title character exhibits his controlling nature through his habit of grabbing people by the backs of their necks to lead them around. Likewise, the artifice of a Nazi “casino” that the cremator visits is exemplified by the unnatural bleached blondes who populate it.

These are far from the only stylistic tricks in Herz’s book. For starters, the film boasts an animated title sequence that anticipates the early work of Terry Gilliam. Also, the centerpiece of the film is a trip by the cremator’s family to a carnival of horrors, which provides Herz with the opportunity to engage in all sorts of visual razzle-dazzle. And, if nothing else, the film is a masterpiece of casting — almost every actor in the film appears to have stepped out of a Charles Addams drawing. Moreover, Herz does not shy from overt symbolism; throughout the film, the cremator is haunted by a woman who clearly represents Death.

Remarkably, these flourishes never overwhelm the narrative or distract from the film’s grim message. The Cremator thus stands as an implicit rebuke to the hopelessly literal-minded and unimaginative “message” pictures that Hollywood unleashes each year at Oscar time. (Jeff, cinemastrikesback.com) ✪

![[Futuristika!]](https://futuristika.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/futuristika.png)